The Chancellor commenced her budget announcement by stating that the route to growth was through investment.

As it turns out, the Uniparty’s investment plans involve weakening the private sector through punitive taxes and burdensome regulations while increasing spending in the public sector. For businesses expecting, or at least hoping for, some respite as the country emerges from post Covid-19 economic constraints and the effects of the Ukraine war, we now know that further hardships are likely ahead. Employers across the country are expecting continued tax increments and stifling regulations to hamper their businesses.

Tax measures such as an increase in Employers’ National Insurance Contributions (NIC) and the Standard Business Rate multiplier impose a cumulative estimated burden of £26.9 billion on employers over the course of this Parliament. Furthermore, earlier proposed legislation to reform employment rights adds restrictions to day-to-day business operations; these measures are expected to reduce GDP per capita by 0.1 percent in the coming year, according to estimates from the Growth Commission.

If we command our wealth, we shall be rich and free; if our wealth commands us, we are poor indeed.

Edmund Burke

Having promised not to increase NICs and personal income tax, the Chancellor had to work out how to fund public-spending ambitions. To that end, she chose to increase the NIC, but for employers only. In doing so, this budget increases employer Class 1 NIC from 13.7 percent to 15 percent and reduces the payment threshold from £9,100 to £5,000. As a case in point, Tesco reported on 9th November that it is expecting tax bills to increase by approximately £1 billion over the course of this Parliament. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates that £25.7 billion will be generated for the Exchequer because of this move. Critics of this statement are left asking: is the juice worth the squeeze?

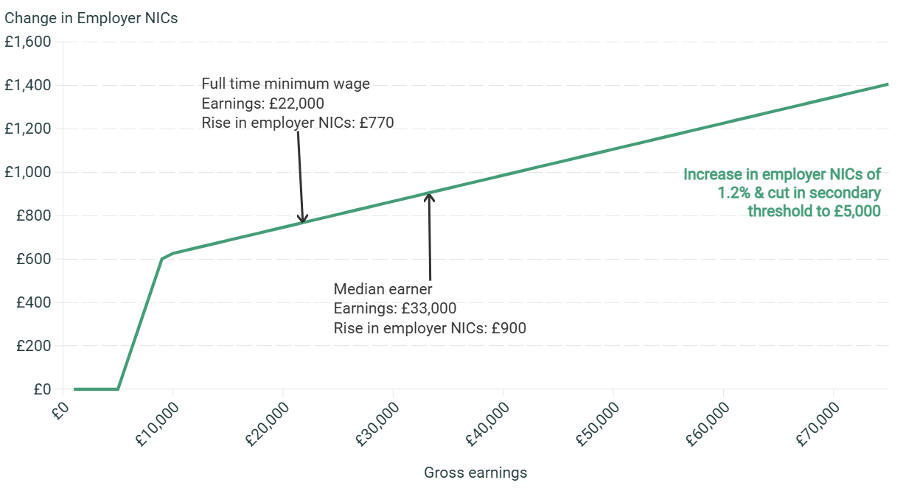

A range of metrics from various research bodies illustrates the possible impact of this tax increase. Figure 1 shows data from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) indicating that employers would have to pay an extra £900 per annum on taxes for every employee it hires on the UK average salary. Furthermore, the OBR review of the Autumn statement shows an estimated 50,000 average hour equivalent reduction in labour supply, thus contributing to growing economic inactivity (currently 21.8 percent, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS)). This National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) shares the sentiment, stating that such taxes would “lead to a fall in job creation and a gradual rise in the unemployment rate”. This would not be surprising: research from Benzerti and Harju (2021) finds that employers react to such tax hikes by reducing employment opportunities for low-skilled work, thus adversely affecting labour supply.

Figure 1: Increase in employer National Insurance Contributions by employee earnings, 2025-26

Source: Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS)

Despite promises of no tax increases for so-called “working people”, these taxes on employers would surely be passed on to consumers. As the OBR estimates, 76 percent of the increases in the Employers’ National Insurance Contribution would be absorbed by consumers, with profits being hit with the remainder of the tax. In effect, the taxpayer faces a new form of tax, exacerbating inflation.

Also announced was the decision to uprate the standard business rate multiplier by the September CPI rate to 55.5p. The Growth Commission estimates that this could generate £1.2 billion in tax revenue. Increasing the standard business rate multiplier is generally considered risky, because it leads to higher taxes for businesses, which can negatively impact their profitability, competitiveness, and ability to invest in growth and job creation. As this increase discourages business investment and expansion, it could have negative ripple effects on overall economic activity and tax revenues in the long run.

These tax measures were presented against a backdrop of the reforms to the Employment Rights Bill introduced in Parliament on 10th October. In an attempt to “upgrade workers’ rights”, this Bill imposes reforms that seek to end zero-hour contracting, tighten conditions for hiring and dismissing staff, and remove provisions designed to insure employers from excess absenteeism and foster employee work loyalty. Sectors such as hospitality and healthcare, which rely on the flexibility that zero-hour contracts provide, risk being severely hit, as they are forced to rely on more expensive alternatives such as permanent part-time contracts. Should the Bill be passed, the Government’s own impact assessment shows that businesses would lose close to £5 billion annually; this figure may be even higher. Estimates on the projected fall in hirings, due to no zero-hour contracting, and impacts of increased strike action, due to repealing measures to hinder such action, are not factored into this impact assessment.

Meanwhile, the Government has increased the national minimum wage by 6.7 percent. This minimum-wage increase risks more expensive goods and services (Forth et al, 2020), reduced profit margins in industries with high labour costs (Wadworth, 2010), and reduced employment (Card and Kreuger, 1994). With personal tax allowances still frozen, much of the impact of this wage increase may be lost, as the new wage rate increases the amount of money being taxed. For employers, this would represent a rise in their NICs by £770 per annum, the IFS estimates. On the other hand, employees are projected to face a potential cut in average wage growth according to Deutsche Bank, which estimates pay- rises to fall by £5.6 billion, with average pay growth falling from 4.75 to 3.75 percent. Thus, neither employer nor employee would truly gain from these wage increases. In fact, this increase in national minimum wage could be seen as an additional tax on businesses. It is no surprise that in a recent survey of 266 companies, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) found, that 66 percent of employers were reconsidering recruitment plans.

So, what is the current outlook for UK businesses following this statement? Business proprietors making succession plans and budding entrepreneurs seeking to start-up in the UK will be met with an increase in the Business Asset Disposal Relief (BADR). Despite warnings from more than 1,000 businesses via the Entrepreneurs Network, the Chancellor chose to increase BADR from 10 percent to 14 percent in 2025, and 18 percent in 2026. In essence, a business seeking to retire or sell their business in 2026 faces an 18 percent Capital Gains Tax (CGT) – an increase of 8 percent from current rates – for proceeds beyond £1 million. This makes the UK a less favourable place to do business in.

The Autumn Budget presents a complex and challenging landscape for businesses, characterized by a series of interventions that appear well-intentioned but potentially counterproductive. The cumulative effect of increased Employers’ National Insurance Contributions, reforms to employment rights, and minimum-wage increases, threatens to create an economic environment that could stifle rather than stimulate growth. By imposing an estimated £26.9 billion collective tax-burden on employers, potentially passing these costs to consumers, and introducing rigid employment regulations, the country risks undermining the private sector dynamism it needs to support.

Many fear there are more tax rises to come. There are concerns that further taxes may be expected in subsequent budgets to redress a potential overspend due to incorrect estimation of core benefits from increasing taxes. For instance, the OBR found that by 2029/30, £16.1 billion would be the true cost of an employer NIC increase after post-indirect behavioural costing (e.g. reduction in profits and wages) are included. Where such tax increases may come from is a matter of conjecture for now. However, what we are left with is the risk of crowding out private investment through fiscal loosening to be replaced with a wider tax burden and an overbearing public sector.

The combination of increased taxes with new regulations which erode the flexibility of Britain’s labour market risks economic pain in the coming months and years. This comes with a backdrop of sluggish economic growth and falling business confidence. Businesses across the country are right to be worried about the path back to renewed prosperity.